Summer in Barcelona. A time of heat, humidity, and the cautious running of that oh-so-expensive air conditioning. Many of my friends, quite sensibly, choose August as the time to take holidays out of the city. But this year, I didn’t have enough money saved to do that, so in between frequent trips to beaches and parks, I’ve been having my own private little film festival instead.

Generally, I’ve been watching at least two films a day. The rule is that, ideally, it has to be a film I’ve never seen. If I have seen it, it has to have been only once, and many years ago (there were a few of these). As we’re coming up to the end of August, and work’s about to begin again, I thought I’d jot down some capsule reviews of the movies I’ve watched, in no particular order. They stretch from the 1930s to 2024, of all kinds of genres, some big budget extravaganzas, some little known indies…

As well as watching movies, I’ve been reading a lot in those parks and beaches. One of the things I found myself caught up in was a Complete Works of Raymond Chandler, and over a week, I read four of his hard-boiled Philip Marlowe detective thrillers. I’ve always loved film noir (it’s why I tend to wear fedoras), so immersing myself in Chandler brought on an urge to catch up on some of the classics I’d never seen…

The Blue Dahlia (US, 1946)

The Blue Dahlia was Chandler’s first (original) screenplay (he’d previously helped adapt James M Cain’s Double Indemnity), and all his usual hallmarks are here. Alan Ladd is the man wrongly (or is he?) accused of his femme fatale wife’s murder, going on the run in seedy 1940s LA with the estranged wife of a local crime boss, with whom Ladd’s wife has also been having an affair.

Trauma, tragedy and bitterness are all thrown into the mix; Ladd, a veteran returning from WW2, discovers that his little son’s death was caused by his wife’s drink driving (which naturally has made her drink even more), giving him a perfect motive to kill her. We aren’t shown the murder, so he might have – but come on, it’s Alan Ladd. Other suspects include his partially brain damaged Navy buddy, a hotel detective, and the aforementioned crime boss and owner of the Blue Dahlia nightclub. This latter is obviously the most likely suspect, so in keeping with Chandler’s usual style, the one least likely to have actually done it.

It sounds great on paper, and indeed it’s an excellent screenplay, full of Chandler’s usual drily witty hard-boiled dialogue. But the execution is rather average. It’s obviously on a lower budget than many noir classics, with cheap sets and a horribly miscast Veronica Lake as the heroine, who often seems unsure of what’s going on around her. It also has a rather muddled conclusion due to studio interference – reportedly a resentful Chandler rewrote the ending in a blizzard of alcoholism, with doctors on standby to inject him with ‘food substitutes’.

The Blue Dahlia is an interesting film for Chandler completists, but by no means a classic.

5/10

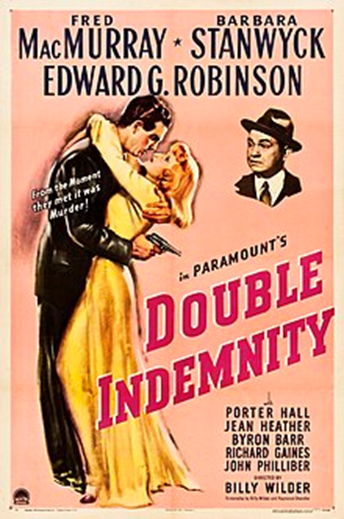

Double Indemnity (US,1944)

That’s more like it. Chandler’s first foray into working with Hollywood (an experience that made him despise the film industry) is a top notch classic. Based on James M Cain’s controversial novel (it had sexy bits in it), Double Indemnity also has the benefit of one of my favourite directors, Billy Wilder, who hired Chandler to polish up the screenplay when the adaptation wasn’t quite working.

Fred MacMurray, previously best known for light comedies, stars as the gullible insurance salesman ensnared in a web of intrigue and murder by femme fatale Barbara Stanwyck (whose bizarre wig is the movie’s only misstep). It was a bold move indeed in 1944 to have the story told from the perspectives of the criminals, and the movie artfully dances around the moral requirements of Hollywood’s Hays Code to at least suggest a rightful comeuppance for them (MacMurray’s is implied rather than shown, even though a scene was shot).

Visually, it’s a treat, all monochrome chiaroscuro to reflect the murky morality of the characters, and accompanied by a sinister score from noir maestro Miklos Rozsa. A top notch supporting cast includes Edward G Robinson as the nominal ‘hero’, playing against type as a good guy for once, and owning every scene he’s in. Justifiably regarded as one of the best movies of all time.

10/10

Lady in the Lake (US, 1947)

An adaptation of one of Chandler’s mid-period Marlowe thrillers, Lady in the Lake guts the complex story that sees Marlowe taken out of his usual LA setting, removing all the scenes set in the lakeside town that form the backbone of the story (we hear about them rather than see them). But it is notable for a very curious reason. Star and director Robert Montgomery made the unusual choice to show the entire movie directly from the visual perspective of Marlowe, meaning that whatever he sees, the audience sees.

It’s a weird point of view experience that doesn’t quite work – it’s very odd when Marlowe is punched or kissed, for example. It does mean that we don’t see much of Montgomery himself (occasionally, when he glances in a mirror), which is probably a good thing – he’s one of the more anodyne performers as Marlowe.

An interesting experiment, but not entirely a successful one – there’s a reason this hasn’t been tried more often. Actually adapting Chandler’s novel isn’t particularly successful either, and this isn’t a classic noir by any means.

5/10

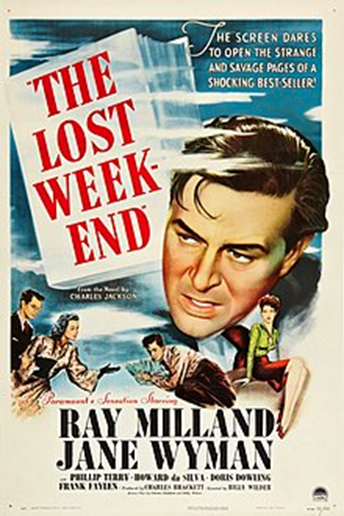

The Lost Weekend (US, 1945)

Billy Wilder again, not working with Raymond Chandler this time but inspired by him. Wilder was staggered by Chandler’s near-suicidal alcoholism while working on Double Indemnity, and chose to adapt Charles R Jackson’s novel to explore the issue. It’s not a crime film, but it definitely qualifies as a noir, what with the murky morality of its central character and some of the more grotesque supporting players.

Once again, this portrayal of the horrors of alcoholism had to play nice with Hollywood’s arbiters of onscreen morality, hence a rather unconvincing ‘happy ending’. But everything leading up to that is grim indeed, with Ray Milland’s failed writer desperately seeking the oblivion of booze despite the best efforts of his long-suffering brother and girlfriend. His sly antics to avoid their discovery of his many hidden bottles are totally believable, and the horrors of ‘DTs’ when he’s finally withdrawing from it are memorably depicted as a gruesome hallucination involving a carnivorous bat and a lot of blood.

Wilder again imbues the film with considerable visual style – I think this was the first time we saw a montage famed around a central character walking dazedly down a street – and his frequent collaborator Miklos Rozsa is again on hand with a moody and downbeat score, which was one of the first to use a theremin.

The novel’s blatant intimations about the homosexuality of many of its characters (particularly the central one) fell victim to the morality of the Hays Code, but Frank Faylen gives an unforgettably nasty performance as a sadistic sanitarium nurse who’s the kind of ‘coded homosexual’ that Peter Lorre so frequently played. That rather twisted view of homosexuality leaves a bad taste in the mouth for a modern audience, but again, it’s reflective of its time.

8/10 (would have been higher, but the compromises required to dance around the Hays Code leave it with a very unconvincing ending)

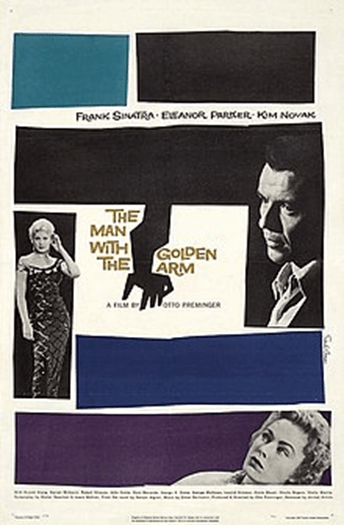

The Man with the Golden Arm (US, 1955)

Another film about addiction, but this time it’s drugs rather than alcohol. Just what drug Frank Sinatra’s addled card dealer is hooked on is left deliberately ambiguous; in the novel, it’s morphine, but what we see in the movie seems more like heroin. Whatever it is, showing any kind of drug addiction in a Hollywood movie was pretty shocking in the mid-50s, and it’s likely this wouldn’t have been made if not for the reputations of director Otto Preminger and star Frank Sinatra.

Unlike The Lost Weekend, this definitely is a crime film, but the crime takes second place to the plotline of the central character’s addiction. Sinatra (who’s perhaps a little too old for the part) plays the memorably named Frankie Machine, a fixture in a low rent Chicago neighbourhood because of his involvement as a dealer in rigged poker games. His best friend is a compulsive thief, and it seems like everyone in the neighbourhood has a hand in some racket or other.

But Frankie, fresh out of prison and newly clean, has a dream of escape. He wants to be a jazz drummer. And he could do it too; if only his addiction (and his poverty-stricken circumstances) didn’t get in the way.

As a study of addiction, it’s less compelling than The Lost Weekend, probably because it’s also focused on a (very detailed) depiction of a certain kind of neighbourhood and its denizens. Once again, the movie has to dance around the Hays Code as to the employment of Frankie’s on-off girlfriend Molly (she’s a “hostess”), but Darren McGavin is a convincingly slimy sharp-suited drug dealer, and Sinatra makes you feel real sympathy for the obviously doomed Frankie.

Preminger is less of a visually impressive director than Billy Wilder, but he nicely encompasses the neighbourhood that’s as much a character of the film as any of the people in it. And possibly the movie’s best asset is Elmer Bernstein’s horn-driven jazz score, which is rightly considered one of his best.

7/10

Marlowe (US, 1969)

Another Chandler adaptation, this time of the novel The Little Sister, Marlowe stars TV’s Jim Rockford, James Garner, as the long-suffering private eye. It’s actually mostly faithful to Chandler’s convoluted plot, but has the novelty of a contemporary setting – no 1940s fedoras and sharp suits here, this is very firmly the Los Angeles of 1969, with hippy communes and Jaguar E-Types.

Well, that’s not too hard to understand. After all, the novel was only published 20 years previously, so it would have seemed quite recent at the time. But there’s a world of difference between the styles, cars and culture of the late 40s and the late 60s. Even so, Chandler’s story seems still perfectly relevant, with the (minor) change of its focus from the movie industry to the world of TV. And in a first for a Chandler adaptation, it’s in colour; lurid, sun-soaked colour of the kind that only late 60s California could provide.

Garner’s no Humphrey Bogart, but he’s a fair Marlowe in this tale of crime, murder and blackmail. As always with Marlowe, he spends his time wisecracking while finding things out – things happen to him, but he doesn’t actually bring anyone to justice. Circumstances – and other people – do that for him.

Gayle Hunnicutt makes a suitably glamorous but rather unmemorable heroine, and of the supporting cast, it’s a hugely charismatic turn by a young Bruce Lee as a perma-smiling, kung fu equipped henchman who makes the most impression. But even though it couldn’t have been the intention at the time, the real star of this movie is 1969 California, and it’s firmly rooted there with all of its squalid glamour.

6/10

The Long Goodbye (US, 1973)

Of all the directors you’d expect to do a Raymond Chandler adaptation, subversive auteur Robert Altman would probably be fairly low on the list. But this 1973 adaptation of Chandler’s own favourite novel, once again given a contemporary setting, isn’t half bad. Granted, there’s far more of Altman here than there is of Chandler, but that’s no bad thing.

Frequent Altman collaborator Elliott Gould stars as a quirkier version of Marlowe than we’re used to, devoted to his pet cat, his vintage Lincoln, and his habit of smoking, and the novel’s twisted plot of alcoholism, betrayal and murder takes a back seat to the director’s love of larger than life characters and reflective dialogue. Caught up in an apparent murder-suicide involving his friend Terry, Marlowe finds himself under suspicion, and investigating the love-hate relationship of Terry’s friends the Wades, while a crime boss is having him followed (with menaces) over a missing $50,000.

That last is a subplot new to the film, and the screenplay, by vaunted Hollywood veteran Leigh Brackett, takes a lot of liberties with the novel. But given the Tarantino-esque long rambling speeches from so many of the characters, I’m betting that Brackett’s screenplay itself took second place to Altman’s free rein style of allowing his cast to improvise.

I was surprised how much I enjoyed this one. It’s by no means classic Chandler, but it is classic Altman.

7/10