“And remember, whatever you do – don’t make me laugh!”

(SPOILER WARNING!)

I must admit, when the “Next Week…” at the end of the previous ep showed what appeared to be a homicidal cartoon character, I wasn’t optimistic about this one. I assumed it would be one of those gaudy, kid-oriented ones Russell T Davies seems to prefer at the moment, all bright colours and no depth. Instead, I was very pleasantly surprised by one of the most interesting, experimental Doctor Who episodes the show has produced since its 2005 revival.

Its mix of animation and live action may be new to Doctor Who, but it’s certainly not a new idea. Plenty have mentioned Who Framed Roger Rabbit, but I fondly remember Gene Kelly doing a dance routine with Tom and Jerry (mostly Jerry) in 1945 musical Anchors Aweigh. What was new and interesting here was a journey through a potted history of animation styles as they evolved, in a manner that was wholly justified by the story.

In retrospect, RTD’s script set that up nicely with Belinda’s reference to Scooby Doo (and the Doctor’s justified rejoinder that he’s far more like the intellectual Velma Dinkley). Of course, a haunted cinema with a reclusive caretaker is basically the archetype of a Scooby episode.

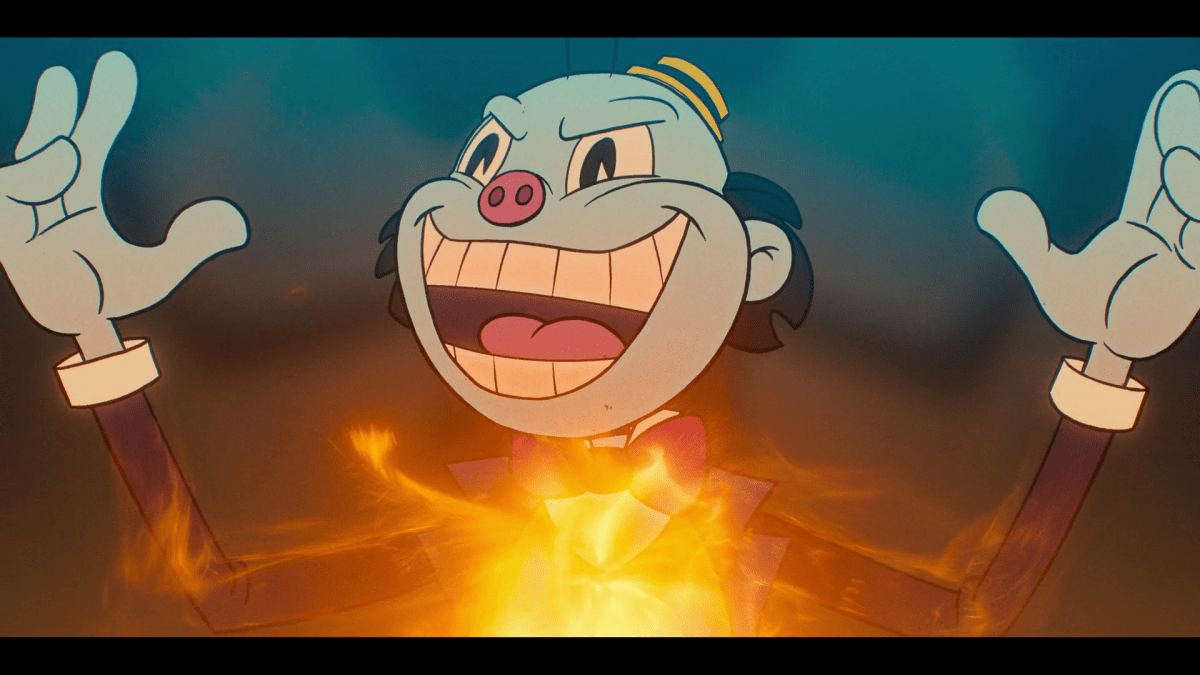

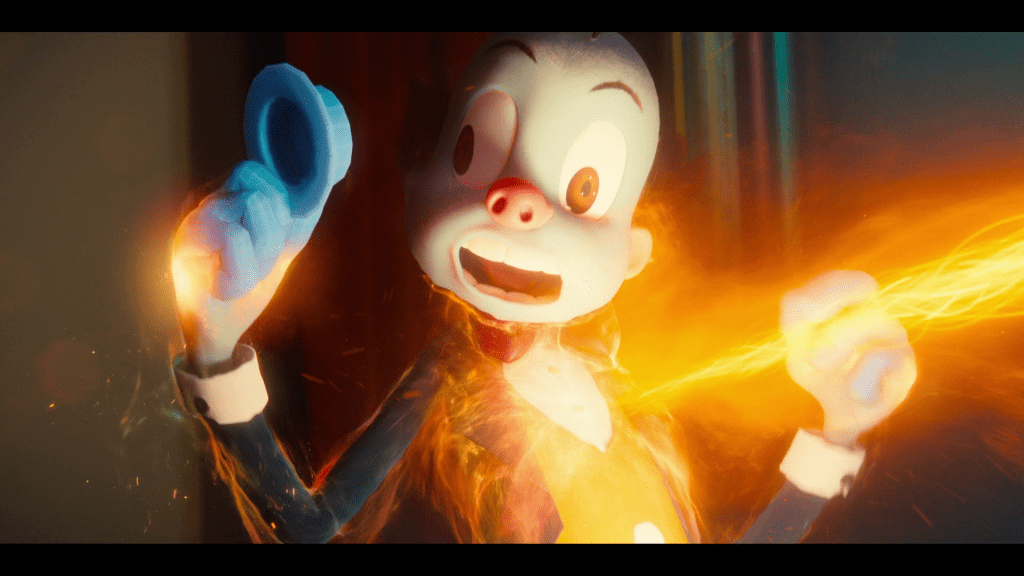

Thus it was that when our heroes were “converted” to animation by the titular Lux, they first appeared in a very 1970s, Hanna-Barbera style. However, as each revealed more of their feelings and backstory, thus gaining “depth”, their animated selves progressed through styles common in the 1980s, then the 1990s. And all in a justified reason as the script paralleled their increasing complexity with that of the evolution of animation.

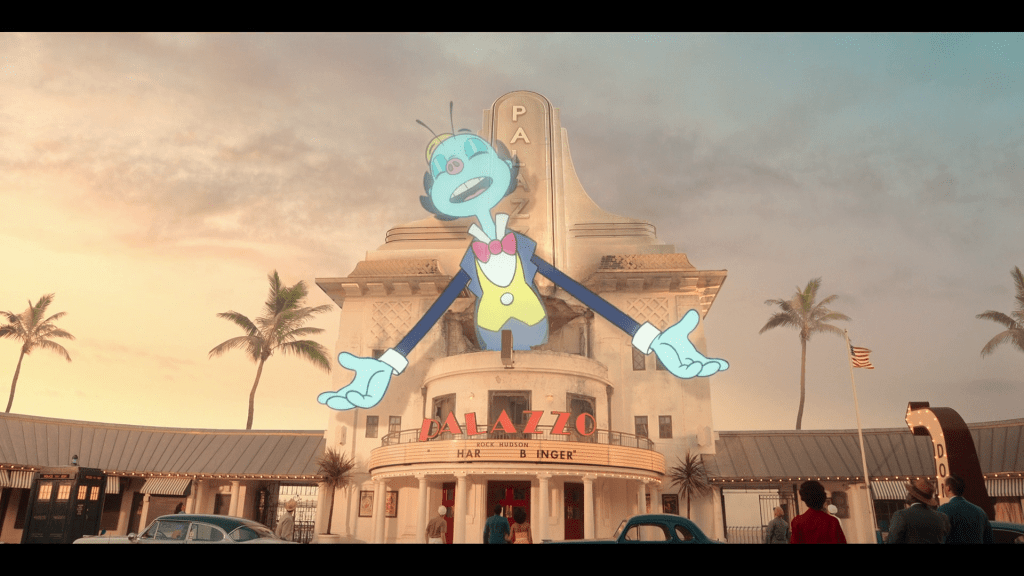

Then there was the eponymous Lux himself. First appearing as a very typical late 30s/early 40s cartoon character (and highly influenced by Max Fleischer’s 1941 classic Mr Hoppity Goes to Town), the scene in which he tried to use the Doctor’s “bi-generation energy” to build a body saw him visually progress through classic animation to modern 3-dimensional CG, complete with line graphics as he changed.

But this subtle depiction of the evolution of animation was only a small part of a very clever script. Again, the notion of being trapped in another medium is hardly a new one – see Sapphire and Steel’s entity that traps people in photographs and burns them alive. Or indeed regular suspect Supernatural, which once trapped its heroes in parodies of other shows scheduled at the same time, then saw them stuck in an actual, existing episode of the very same Scooby Doo.

So the fate of the fifteen initial victims of Lux was hardly a surprise, when Belinda found them trapped in celluloid like flies in amber. But her and the Doctor’s various attempts to escape their own celluloid confinement was some of the more inventive playing with form the show’s ever done, as they flipped through frames frantically, then ultimately held one frame still enough for the projector’s light to burn it out.

All that of course led into the most talked-about scene of the ep, as the Doctor and Belinda found themselves emerging into (what seemed to be) the real world, meeting a trio of dedicated Doctor Who fans who were in the process of watching this very episode. It was beautifully done, as our heroes’ hands appeared to push at the very inside of our TV screens themselves, then the “glass” barrier toppling and their emergence into a typical Who fan’s living room, complete with (real) DVDs and Blu Ray box sets of the show.

It’s about as meta, fourth wall-breaking as you can get, and has predictably caused the most controversy as some fans struggle with how they were depicted onscreen. In truth, Lizzie, Hassan and Robyn were a truly likeable trio of characters, so I don’t see a problem with it. And like the earlier, similarly divisive paean to the show’s fans, Love and Monsters, RTD seemed to be gently lampooning the show’s fans from a place of genuine love.

He also got to pre-empt the reviewers’ usual complaints about his writing, with Robyn’s complaint that the story’s ending was clearly signposted from about halfway through (which turned out to be true). And in the process, even had a gag at his own expense, when the trio of fans all agreed that the best episode ever was Blink – one of Steven Moffat’s. RTD may have said that he doesn’t want to constantly hark back to the show’s past, but hopefully newer viewers may now be seeking out this 18-year-old classic ep to see what the fuss was about.

And the trio’s self-awareness that they themselves were just fictional characters who would cease to exist when the Doctor and Belinda left (prompting one of Ncuti Gatwa’s trademark tears) was actually heartbreaking, and worth breaking out one of Murray Gold’s best cues from the Matt Smith era for.

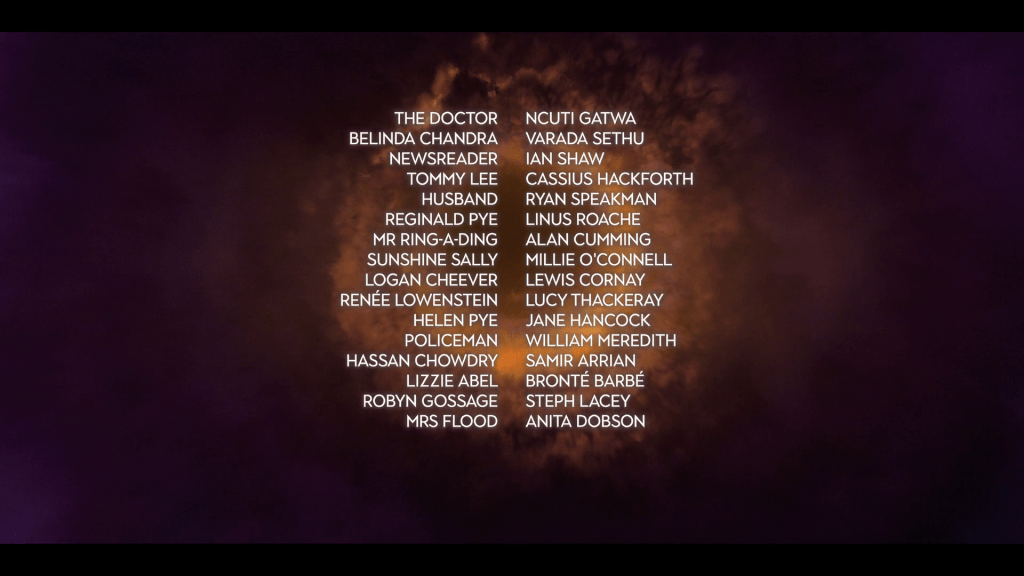

Some fans (probably the same ones who complained that Russell was making fun of them) have complained that the script broke its own rules by allowing them to survive at the end of the story, and yet that makes perfect sense in the most meta of ways. “We’re the sort of characters who don’t get surnames,” laments the all-too-genre-aware Lizzie – yet in the actual credits, there they are. With surnames. As if the writer himself relented and allowed them a new lease of life within genre rules.

Your mileage may vary as to how tolerable you find this kind of meta fourth wall-breaking. It may be new to Doctor Who, but other shows, notably Supernatural again, have shown alternate realities mirroring our own, in which the show’s characters are just that – characters in a popular TV show. But the ep wasn’t entirely dependent on that clever-clever conceit. There was a real story, with realistic characters, and a believable depiction of an era that’s both glamorous and dark to modern sensibilities.

I was glad that the script didn’t shy away from depicting the very real fact that segregated early 50s Florida was not a good place for people of colour to be (unlike the irritating erasure of the equally real 19th century racism in last year’s “Bridgerton episode”). It was straining credulity somewhat that this was such a shock for Belinda, but fair’s fair, the show’s younger audience needed this explaining to them. And the reference to the tragic story of Rock Hudson was nicely underplayed; I’m glad it was there, but the details were sparing, so anyone interested could go and look up the sad truth rather than having it spelled out in a laboured way.

The Doctor and Belinda’s relationship continued to develop in a nicely natural way, from Belinda’s grudging acceptance of the Doctor’s eagerness to investigate the shuttered cinema to her concession that she may not be in such a hurry to return to her proper time. Their animated discussion (pun very much intended), in which the Doctor admitted to being “not just a Time Lord, but the last of the Time Lords”, was very much a callback to earlier RTD episodes where that was true, before the on-again-off-again return of Gallifrey – will it stay gone this time?

Gatwa and Sethu continue to be a good pairing, with a natural chemistry that allows for Belinda to be far more disagreeable to the Doctor than Ruby Sunday, without losing our sympathy. And like last week (in another echo of RTD’s earliest stories), it was Belinda who saved the day while the Doctor was held incapacitated. True, that resolution had something of the “Davies ex machina” to it; while the flammable film stock had been established earlier, the viewer had no reason to expect that exposing Lux to daylight would cause him to dissipate across the universe.

Still, it fit nicely with Lux’s earlier teasing that the key to his defeat was in “what I don’t do”. Lux was a fun baddie who fits in with the show’s current “pantheon” of godlike beings, preceded by the Toymaker and the Maestro. I don’t mind this as much as I used to – I initially took it as a rejection of the show’s firm philosophy of rationality over superstition, but the Doctor’s description of the “gods” here was very much in keeping with various other godlike beings we’ve seen in other shows – notably Star Trek Deep Space Nine’s Prophets – so it’s not entirely inconsistent. Plus it was amusing that veteran star Alan Cumming’s much-touted guest appearance was actually a voice role – and not even in his real, Scottish, accent!

The other guest roles (in a small roster of characters) were perhaps less rewarding. West End theatre star Lewis Cornay was engaging as late-night diner worker Logan, but it wasn’t much of a stretch of his acting ability, while Lucy Thackeray’s Renee Lowenstein was little more than “grieving mom”. The only one who did get some depth was Linus Roache’s melancholic projectionist Mr Pye, trapped in an illusion of his resurrected wife (to the soundtrack of the much-recorded Girl of My Dreams, best known to me as the dark heart of Alan Parker’s Angel Heart). Mr Pye got an actual character journey, realising he had to redeem himself by no longer living in the past. Message, Russell?

Of course we couldn’t go a week without a sighting of Anita Dobson’s Mrs Flood (guilty of her own fourth wall-breaking last week), who once again spoke directly to the audience, warning us that the show “ends March 24th” – the broadcast date of the penultimate ep, the first of a two-parter. Again, Steven Moffat already did this with Amy Pond’s wedding date, but it’s a nicely meta reference in a particularly meta episode.

Lux was a dazzlingly inventive Doctor Who episode that worked on so many rewarding levels. If all you wanted was a simple story about an imaginative baddie to be defeated by the Doctor, sure, that was there. But if you wanted it, there was so much more here – a tribute to the history of animation, an examination of the show itself and its fandom, a depiction of a seemingly nice period of history with very dark undertones. I can understand why some people may have thought it was perhaps too clever for its own good; but for me, that was the best script Russell T Davies has done in his second go-round as showrunner.