On April 28, I was walking back from the shop at about 12:40 when it happened. As I looked down my street, I saw all the illuminated signs and interior shop lights flick off. Shopkeepers emerged, blinking, into the bright daylight, glancing up and down the street to see if they were the only ones affected.

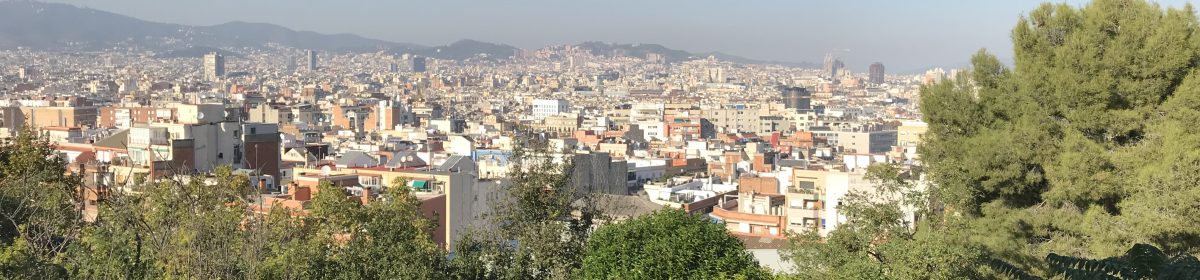

At the time, I wasn’t too worried. Small, localised power outages, while not frequent, do happen in central Barcelona. Usually, at most, a few buildings, perhaps an entire street, not usually lasting too long. I had an important online meeting at 13:00, but I wasn’t too worried; I could use my laptop’s battery, and connect by tethering it to my phone’s 5G network.

When I tried, though, I got my first inkling of unease. My phone signal was nonexistent, which is very unusual – it’s usually excellent in my apartment. I went up to the roof, and tried there. Still nothing.

I still wasn’t too worried. I knew that 5G signals are routed through a network of transponders attached to buildings – perhaps the local ones had also suffered a power cut. Shrugging, I realised I would have to miss the meeting, and sent an email of apology with no idea when it would be received. I had a bunch of unread comics on my iPad, so I settled down to see exactly what was going on in IDW’s Star Trek crossover for as long as the outage lasted.

I didn’t know then of course, but it was going to last a lot longer than I expected. And be… a little more widespread than just El Gotico. I had afternoon and evening classes, and my job is a 16km journey out of town to the technically separate city of Sant Just Desvern. I’m currently suffering quite badly with sciatica, so I’ve been taking the Metro rather than my usual e-scooter; heading towards Urquinoana Metro, I noticed that the lights in the shops and cafes were off everywhere. Traffic lights were off too. A larger amount of people than usual were roaming the streets, and I noticed many of them waving their phones in the air, that modern dance of desperately searching for a signal.

When I got to Urquinoana, I found the Metro entrance gated off. Clearly this was a much bigger problem than I’d thought, but without a phone signal, I had no way to check how big. It made me realise how dependent we’ve become on these all-purpose devices, and the internet they access. It didn’t even occur to me to look for somewhere with a radio; but of course that wouldn’t have helped either, unless it was battery powered.

Arc de Triomf Metro isn’t too far away, so I wandered over there to see if it was only Urquinoana station that was shut. It wasn’t. Arc de Triomf was shuttered too, baffled tourists milling around in huge groups outside. It occurred to me that I could take the bus, but then I realised that without my phone, I had no way to find out which bus I would need, or where it went from. In any case, every bus stop I passed was thronged with people, while buses drove by without stopping, crammed with passengers, their faces almost pressed against the windows in the crush. Obviously buses weren’t going to be a solution.

There was nothing for it. Despite the pain in my back, I was going to have to use the e-scooter. I still had plenty of time, as it takes about half the time public transport would, so I headed home. Collecting the e-scooter from my third floor apartment (which doesn’t have a lift), I winced at the pain in my back as I carried its 14kg weight down the stairs. Has to be done, I thought. And of course, even if I’d had a lift, it wouldn’t have been working; I later found out that hundreds of people across the country had had to be rescued from lifts stalled between floors.

As I set off, I noticed people were gathering in concerned groups in the street, sharing as much information as they had. I didn’t have time to stop, so I pressed on by my usual route, which, it turned out, was a lot more hair-raising than usual. Barcelona has quite a good cycle route infrastructure, but it uses the same traffic lights as everyone else at its numerous junctions, and none of them were functioning.

Police officers of every kind had been pressed into service to direct the traffic at some of the larger junctions, but by no means all of them – I’d guess there simply weren’t enough police for that. At the unmanned ones, I was surprised to find Barcelona’s usual hectic traffic was moving slower than usual, cars courteously stopping to allow pedestrians to cross the streets. If, that is, they had the nerve to tentatively start walking into the road. Many people were just standing helplessly at intersections until someone took the lead.

All that goodwill from drivers taking it slower had consequences though. Gran Via de Les Corts Catalanes was completely gridlocked as strained looking cops struggled to control the bigger junctions. With no traffic lights, the vehicles trying to turn onto it from the intersecting streets were gingerly pushing their way in, creating a bigger traffic jam that widened out from the main thoroughfare. I imagine this was repeated throughout the city on every major road, bringing Barcelona traffic to a near standstill.

Those of us on e-scooters and bikes did have an advantage – we were small enough to weave through the chaotically placed cars blocking every junction. And again, somewhat to my surprise, drivers were watchful and courteous enough to us for that to be possible. In turn, we took things a good deal more cautiously and slowly than usual, mindful of the people trying to cross in front of us. Even the normally maniacal delivery riders were actually going at less than their usual frantic, illegal speeds.

The gigantic, light-controlled roundabout at Placa Espana was another scene of chaos, as cops tried their best to balance traffic trying to enter from its six massive intersections with pedestrians trying to cross. As I got through it and headed up the big N-340 city road towards Sant Just, there was still no power anywhere. And still no information. OK, I thought, this looks citywide. But Sant Just Desvern is technically outside the city (not that there’s any visible gap between them), so perhaps the power would be on at work.

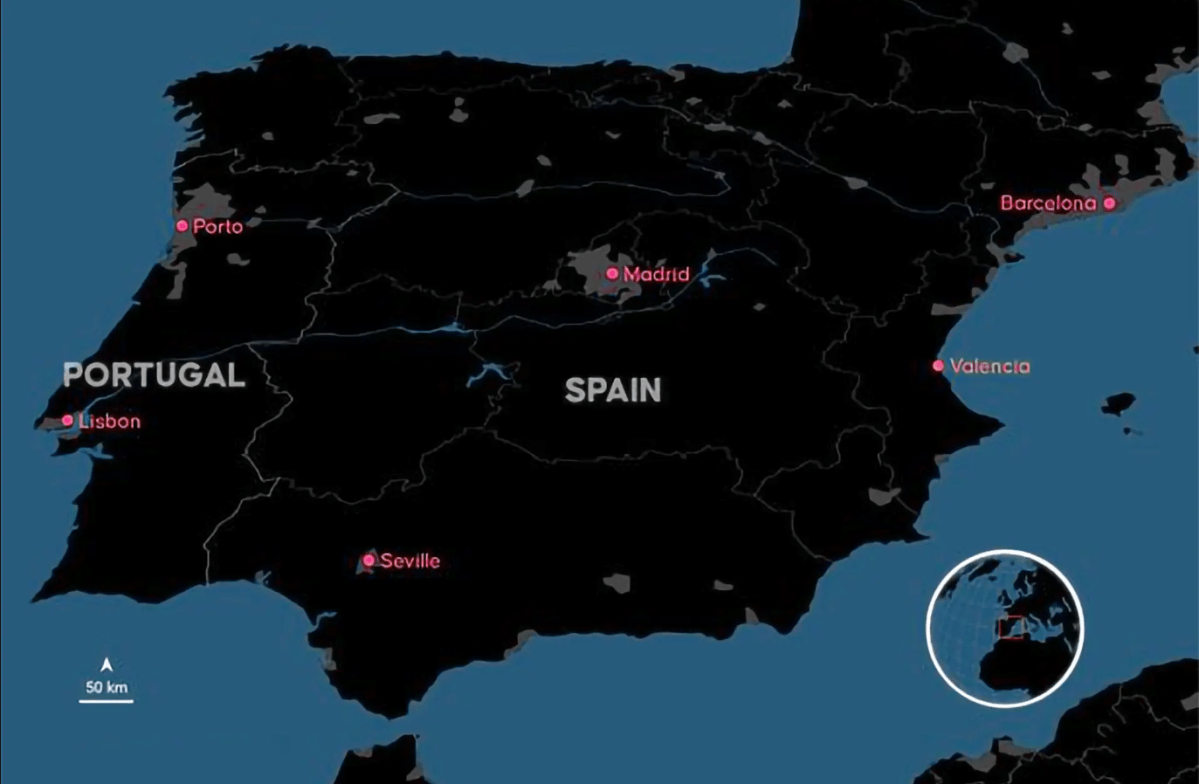

I was distracted by a vibration from my pocket. Had the phones been restored? Pulling up, I checked my phone. Still no signal; it had obviously just been a blip. But there was an ominous BBC News notification on the screen – “Madrid mayor urges people to stay put and keep off roads – live updates on power cut chaos across Spain and Portugal”. Uh-oh. This was clearly a lot bigger than just my barrio, or the city of Barcelona.

I no longer expected the power to be on when I got to work, but I was about three quarters of the way there, so I thought I might as well press on. Outside the city centre, it actually turned out that the non-functioning traffic lights were making the traffic run more smoothly, as nobody had to wait on a red even though there was no traffic going the other way, or no pedestrians crossing. Without the sheer volume of traffic in the city centre, it seems that the absence of traffic lights can be an improvement. It made me think that perhaps Barcelona has more of them than it needs, since drivers appeared perfectly capable of using junctions, and pedestrians were perfectly capable of using crossings, without them.

Because of that, I got to work in good time despite the city being much slower than usual. At my academy, the few colleagues already there were none the wiser about what was going on. At least one other teacher hadn’t arrived, but without communications, we had no way to check if students were still expecting classes to be on; we had to stay just in case.

My colleagues shared what information they had, which was mostly hearsay, and, it later turned out, often wildly inaccurate. The power was off in France too, said one, while another said it was worldwide, including the United States. “Russia too?” I asked, somewhat sarcastically. “No”, replied my colleague, with a dark, knowing nod. Nonsense of course, but it turns out that word of mouth is just as good at spreading misinformation as the internet. I dread to think what mad theories might have emerged if this had all gone on longer.

Fortunately, the boss turned up and took very effective charge. We would teach classes as usual, she affirmed, just without the technological bells and whistles we’ve become used to. That meant Speaking and Reading classes from the books, with a lot more writing on the board than I’m accustomed to. We’ve become spoiled by online course books that you can project onto the whiteboard – this was analogue teaching, just like it used to be.

My working day on Mondays finishes at 9pm, with an hour or so Journey back home on the e-scooter. That worried me – daylight is quite long here, but it would be dark when I finished, and I didn’t fancy scootering back across a pitch black city with no streetlights. However, the few kids who’d turned up for my early evening class let out a ragged cheer when the lights flickered on at about 6:30. Assuming that meant the restoration of power everywhere, I went on to teach my evening classes, relieved it was all over. The last one at school, I locked up and posted a Facebook status about my chaotic day, with all seemingly back to normal.

How wrong I was. I found out later that power had returned to different parts of the city – and, presumably, the country – seemingly at random. The first inkling I had of this was when I turned onto Sant Just’s main street to discover it was pitch black. Just as I’d feared earlier, all the streetlights and traffic lights were still off. Car headlights provided some illumination, but not much; it seems many people had stayed in, so there were far fewer vehicles on the road than usual. That meant my only source of light was the small headlight of my scooter, which isn’t meant so much for illumination as to show the scooter’s presence to drivers. Scarcely able to see more than a few metres in front of me, I edged along the wide cycle path of the main street much more slowly than usual.

The lights, and traffic lights, were back on at Finestrelles shopping centre. Then off again on the hill down to Ernest Lluch Metro. I noticed trams standing idle at the stations where the road runs parallel to the tramlines, presumably stuck there since the early afternoon. The police, having not enough officers to man all the junctions, had come up with an alternative solution, and many junctions were blocked off with cones and/or police tape. That made my route more circuitous than usual, and also ensured I continued at a very low speed – you couldn’t see the tape or cones until you were almost on top of them.

The pattern of lights being on again and off again at random continued from block to block, but most of the usually busy N-340 was in total darkness. When you watch post-apocalyptic dramas set in dark cities at night, there’s always a dim, blue hint of moonlight so the viewer can see what’s going on. In reality, it’s not like that. It’s pitch black. And as before, there were far fewer cars than usual to pierce the darkness with their headlights.

Here and there, I could see knots of people walking carefully down the sidewalks, waving phone lights ahead of them, to see where they were going and to warn others of their presence. Some had the good sense to wave these into the road as an indicator that they were crossing; most didn’t, so I had to continue very slowly as dark figures suddenly loomed up walking over the road, their silhouettes only visible when you got quite close to them. Despite the danger, I didn’t see a single accident or mishap. Not a horn went off, nor a shout went up. I was being very careful, so were the drivers, and so were the pedestrians.

The lights were still mostly off at Placa Catalunya and Las Ramblas (not that it had discouraged the tourists), but I was relieved to see the power was back in my barrio of El Gotico. I had worried I would be unable to eat; most residences in Barcelona have only electric cookers, and with no power to the shops, they had all closed – no chance of buying anything ready to eat.

A few shops had gamely stayed open, using battery powered LEDs for illumionation. But of course none of their card machines were working, so it was cash transactions only. And who carries cash these days? If you wanted any, you were out of luck – there was no power to any of the ATMs either. It made me reflect, for the umpteenth time that day, how our dependence on technology for convenience has left us hugely vulnerable. I think I might take to keeping a 50 euro ‘float’ in my wallet at all times for emergencies.

The power was indeed back on in my apartment, luckily, so I microwaved my leftover sweet and sour chicken in some relief. We weren’t so fortunate with the internet, however. Phone signals were still sporadic, and servers went up and down. I tried watching a Doctor Who blu ray, but my blu ray player is a computer drive and its software won’t function without internet access. Eventually I gave up even trying, and watched some old episodes of the 1984 Sherlock Holmes that I had on a memory stick. It was inconvenient, but I was probably far better off for entertainment than the majority, who stream everything these days without keeping local copies. Thus it was that I had something to watch while my roommate sat in bored silence, unable to access his beloved YouTube.

So that was how it went for me on the day everything went off on the Iberian Peninsula. I must say, I was impressed with what must have been a huge effort to get everything working by the next morning, which it was. It transpired that this wasn’t a Russian or Chinese cyber attack, nor had we, as I imagined in some of my more paranoid moments, been targeted by an alien space fleet shutting off power worldwide. Just a freak atmospheric issue that tripped a generator here, causing a surge there, leading to a chain reaction that plunged Spain and Portugal back to the technological level of the 1970s.

Except in the 1970s, people could have coped better. They had landlines, and pay phones (all gone from the streets of Barcelona), battery powered radios and stereos. I’ve been struck by just how vulnerable our hi-tech society is when even people in 1975 would have been better-equipped to weather such a calamity. Even if they did have questionable fashion sense and some pretty terrible cars.

Despite the chaos though, all this showcased the real sense of community this city has. People were watching out for each other, trying to ensure everybody’s safety. Barcelona has a (well-deserved) bad reputation for things like street crime, but a situation like this showed it at its best, with everybody pulling together. I experienced the same feeling during the (much longer) lockdown. It just made me more sure how happy I am with this city as my home – even when things like this happen, it’s just another part of the adventure.

NB – I didn’t have the chance (or the nous) to take any photos during all of this, so any pictures here are from a variety of internet sources too numerous to mention. Thanks in advance to all, but if anyone wants one removed, just let me know in the comments.