“You must tell a story, Doctor. You must feed it. It is always hungry.”

(SPOILER WARNING!)

“Why are Earth people so parochial?”, wondered the Fifth Doctor in 1982’s The Visitation. In fact, the accusation could just as easily have been levelled against the show itself in its original run. Obviously, there were practical and budgetary reasons why every alien invasion of Earth seemed to centre on South East England (“They’ve turned the whole of Bedfordshire into a gigantic mine area!”).

And while the show, in its early years, did try to depict different cultures, it was always in a historical context as viewed through a very British prism. I love The Aztecs and The Crusade as much as the next fan, but it has to be said that their respect for the cultures shown is nowadays rather undermined by the unfortunate (but perfectly acceptable at the time) casting of white actors in black makeup as historical figures like Saladin.

The new show, with its more international funding, has gone some way to redressing that. BBC America made it possible to film in the US, but despite the uneven respect for his era, Chris Chibnall was at the forefront of finally showing us stories set outside the white Anglosphere, with the excellent Demons of the Punjab.

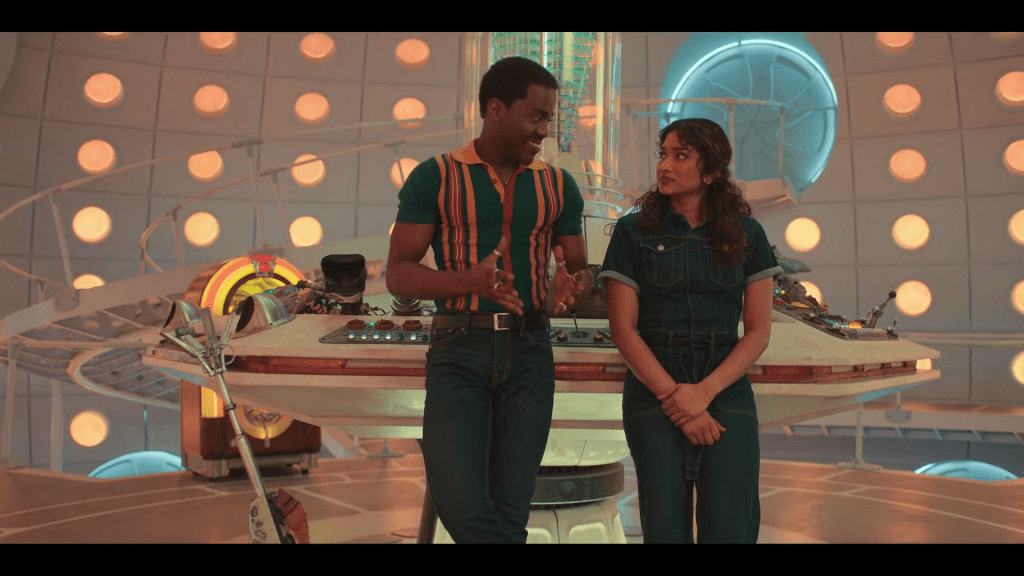

The Story and the Engine very much builds on that, with its main setting of Lagos. In doing so, it explicitly touches yet again on the fact that, in this current body, the Doctor may not be finding it so easy to blend in everywhere on Earth as he used to. “It’s the first time I’ve had this Black body,” he confides to Belinda, “and in some parts of the Earth I’m now treated differently”. So he has a fondness for Nigeria because “here, I’m accepted”.

It does seem odd, though, that this most sexually fluid of Doctors seems to have somehow missed that Nigeria is one of the most homophobic and transphobic countries in the world, where gay people can legally be stoned to death. Mind you, longtime fans of Ncuti Gatwa may remember his Sex Education character Eric Effiong making a trip to his home country of Nigeria (Gatwa himself is of Rwandan ancestry), where Eric had no trouble pulling and had a whale of a time at an underground gay club. Obviously, while the law (a legacy of British colonialism) may despise homosexuality, not all the people do. Still, though, I wish something had been mentioned about this, rather than “pinkwashing” an institutionally homophobic nation.

To be fair, that wasn’t part of the agenda of this interesting, metaphysical episode, which touched yet again on gods and the power of belief. Nigerian writer Inua Ellams’ imaginative script was one of the most inventive I’ve seen since 2011’s similarly surreal The Doctor’s Wife, and with its intertwining themes of different cultures’ folklores, the power of stories and belief to fuel gods, it was inescapably reminiscent of other work by that story’s writer, Neil Gaiman.

I must admit, I’m conflicted about comparing this to the now disgraced Gaiman, and about the fact that, no matter how awful a human being he has turned out to be, I still find his work admirable and inspirational. But given that this was filmed in 2024, any inspiration Inua Ellams took from him was before those allegations had come to light.

And it may have been nothing more than a coincidence, of course. Gaiman may have written an entire novel about African trickster spirit Anansi, but as an African writer, it was perhaps obvious that this aspect of folklore was the one that dominated Ellams’ script. Not only did we get the visual representation of the Barber’s transdimensional craft as a giant spider travelling along a “worldwide web”, but Abena (Michelle Asante), and her relationship to the spider god was a key plot point.

To be fair, this may have been a little unclear. If Ellams’ script had a weak point, it was that so much was going on, explanations were rushed and easily missed. So, the Barber had once been a human being, who was responsible for chronicling all the stories of the gods, reinforcing the human belief that they needed to survive. Finding himself rejected by them, he’d constructed a metaphysical yet actual web to get to the Nexus of human belief where he could destroy them in vengeance for that rejection, powered by stories from inside a barber’s shop that existed simultaneously in “space” and Lagos, which only he and Abena could leave. And the Doctor had to stop him, because without the stories of the gods that are so much a part of humanity’s culture, humanity would be unable to survive. Phew. No wonder the Radio Times felt they had to publish an article explaining it.

Actually though, I felt it was clear enough if you were paying attention, though perhaps a little complex for the very young viewers the show often seems to be pitched at. Yes, it was very surreal (though no more so than The Giggle or The Devil’s Chord), but I think I might have actually been helped by my familiarity with the work of Neil Gaiman, who introduced me to much of the folklore explored here. Plus, both his comic The Sandman and his novel American Gods have as a central plot point that the entire existence of the gods is dependent on the belief of humanity. So, whether inspired by Gaiman or not, Ellams’ use of it as a plot point here felt perfectly comprehensible to me.

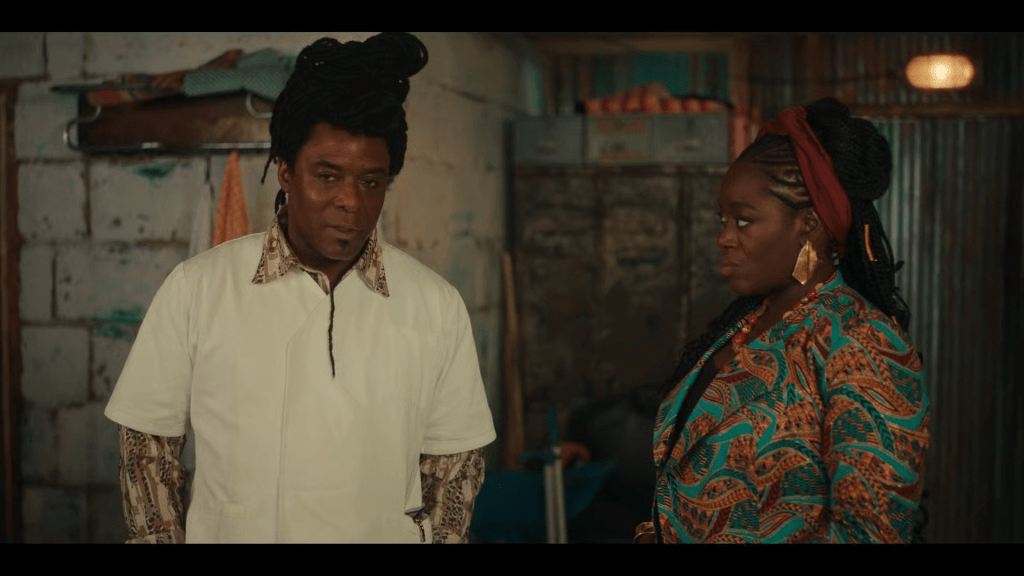

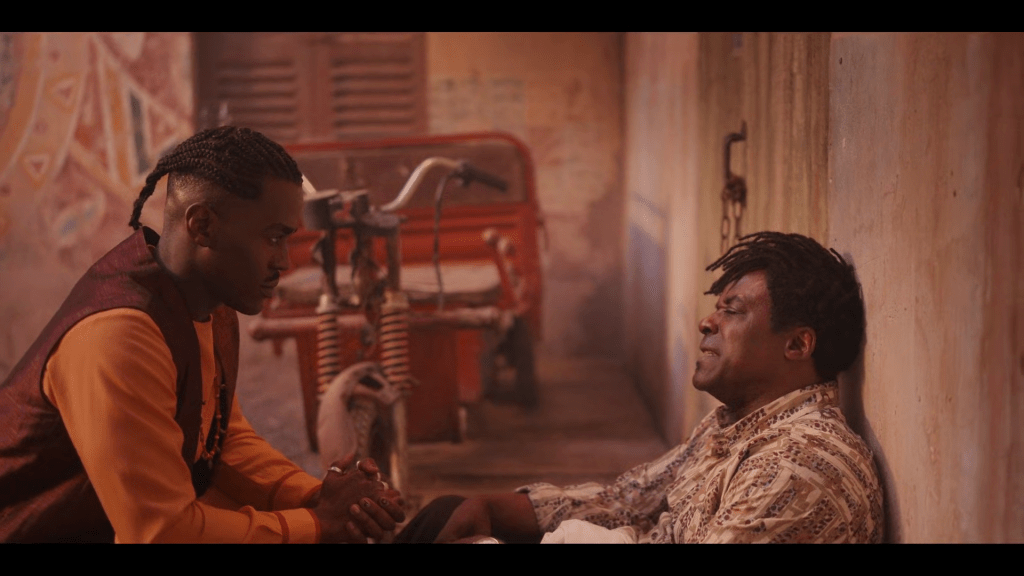

It helped that it was grounded in a very believable, ordinary supporting cast, outside the mysterious Barber and Abena. Principal among these was Sule Rimi’s Omo Esosa, an old friend of the Doctor who went through his own arc of betrayal and redemption. The Barber himself was a magisterial performance from Ariyon Bakare, who appropriately dominated the screen whenever he was on. One notable aspect here was that, outside the Doctor’s visualised story about Belinda, none of the characters were white. Mind you, of course we had to get the inevitable cameo from Mrs Flood, here reduced to ‘coincidentally’ bumping into Belinda, which somehow the Doctor missed despite it being clearly displayed on the shop window.

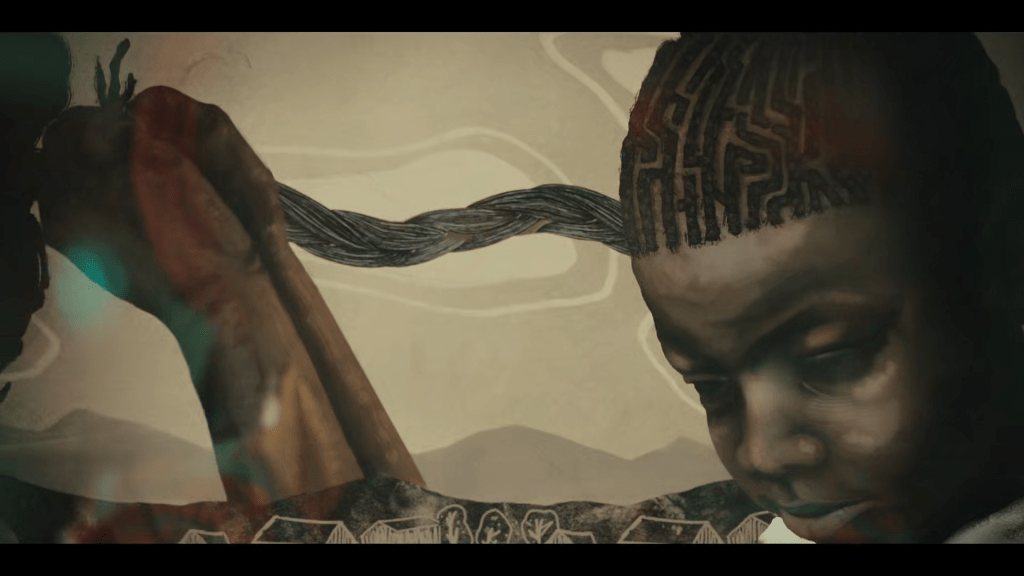

In fact, that was one of the duller representations of the stories being told to fuel the Barber’s arachnid craft. The others were beautifully realised in animated forms pastiching traditional African art; none more affecting than Abena’s story of the slave women weaving escape maps into their own hair, which was so vital to the story’s resolution.

On a less serious note, all this finally explained something more pedantic fans may have been wondering for some years – just how does the Doctor get his hair done? This Doctor in particular seems able to go from short to long to short in the blink of an eye. Well, now we know – the TARDIS does his hair! I don’t know what the Ship was thinking when giving Pertwee and Capaldi those giant bouffants, but at least we now have an in-universe explanation for why Davison’s hair goes from long to short to long again in the space of his first three stories 😊

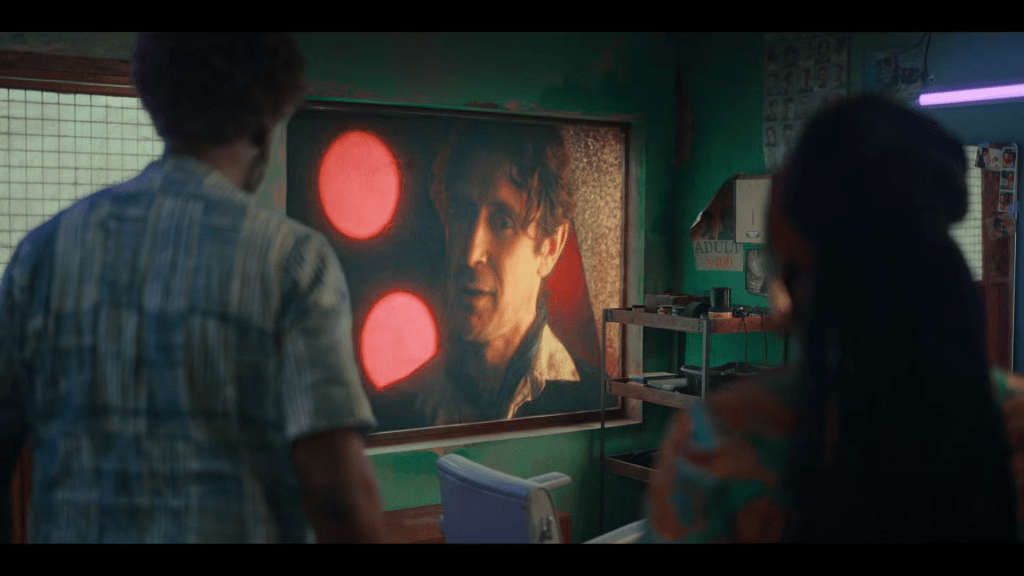

And we had plenty of opportunity to study those hairstyles in the story’s perfectly logical resolution. Of course the Doctor’s own story is ‘neverending’ – and just to prove it, we were treated to visual displays of every Doctor in the show’s history on the craft’s screens. That’s just TOO MUCH story – no wonder the story engine overloaded.

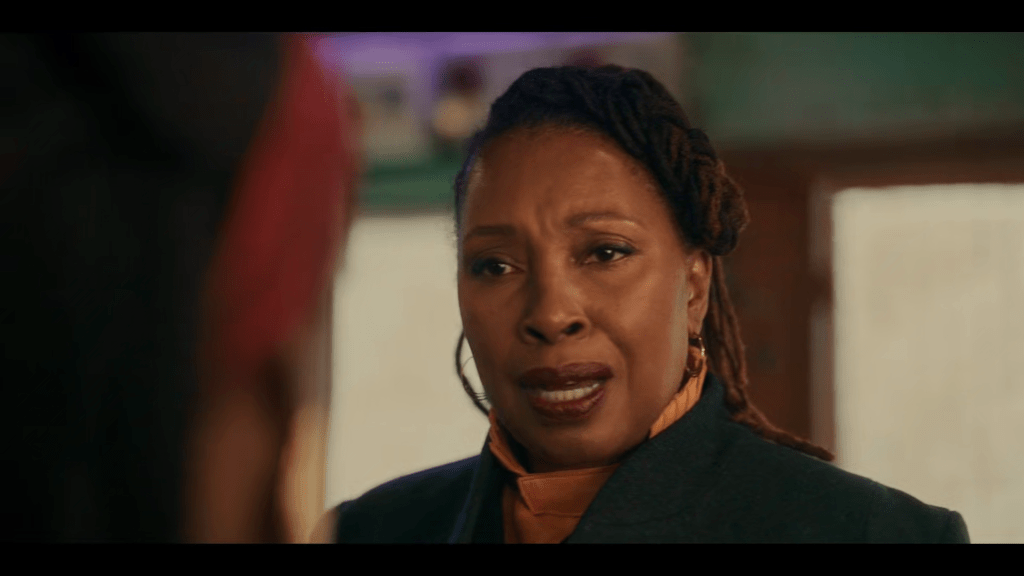

The icing on the cake, though, was an unrelated callback to the show’s past when Abena confronted the Doctor about his failure to protect her from Anansi’s bet. I let out a little cheer when, panning around Abena’s back, we saw the relevant Doctor at the time – none other than a surprise comeback for Jo Martin’s magnificent Fugitive Doctor. Her creation was, for me, one of the most memorable aspects of Chris Chibnall’s uneven run on the show; and I’m glad to see that it’s another one Russell T Davies has carried on. Let’s hope this isn’t the last time we see her.

I’ve seen some friends disappointed about the Doctor’s treatment of Conrad at the end of the previous episode, calling his behaviour “spiteful and vengeful”, and out of character for this incarnation. I disagree – this may be a new incarnation, but it’s still the same Doctor who meted out some pretty dreadful punishments to the likes of the Family of Blood.

Still, if you felt that way, you might have been reassured by his ultimate forgiveness here not just of his old friend Omo, but more pertinently, the chastened Barber, now condemned to living a normal life in the real world. Mind you, it has to be said that the Barber was genuinely repentant, with the Doctor having shown him how to redeem himself; while Conrad, given every chance to atone, remained the same nasty piece of work he was at the beginning.

I loved The Story and the Engine, but I’m guessing not everybody will. Oh sure, there’ll be the usual “anti-woke” idiots objecting to seeing a different culture with people of different skin colour. But I think there may be more than a few fans decrying the story’s embrace of outright fantasy as “not proper Doctor Who”. I don’t mind that, and it’s been the way the show’s been going since Russell T Davies returned. But I appreciate it may not be for everyone, in a show that has always had rationality and science at its core.

Shows evolve, though. And having just rewatched 1971’s The Daemons, I think it’s perfectly possible for a story to balance science and fantasy in a satisfying way. After all, as Arthur C Clarke famously said, “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. It’s the same reason I so enjoyed The Doctor’s Wife, and the other work of Neil Gaiman, which this reminded me of so much – I just wish I could square the circle of who we now know him to be with his genuinely beautiful work. At least Inua Ellams has no such issues, so I have no problem saying that I found this one of the most interesting and inventive stories of recent years.

Oh, and, if you’re wondering – that six word story by Hemingway goes like this:

“For sale: baby shoes, never worn”.

Only trouble is, Hemingway never wrote it. It’s a perfect example of how stories can come to be more powerful than facts.