“To be, or not to be…”

(SPOILER WARNING!)

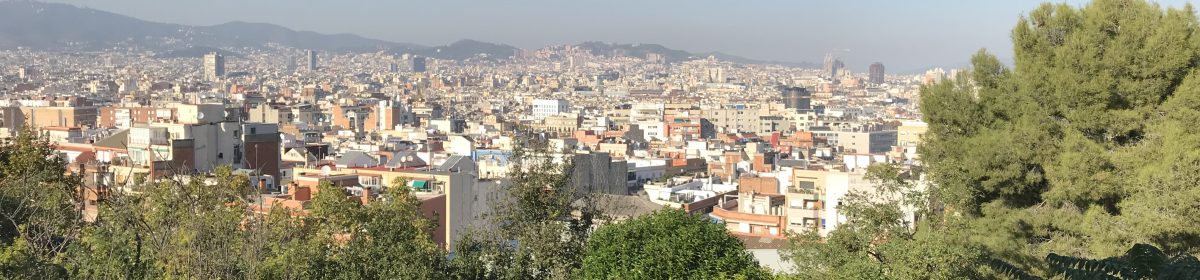

It’s my annual season for checking out the Oscar nominated movies before the ceremony. I never get through all of them, but I often encounter interesting films I wouldn’t otherwise have seen – this year, I was particularly impressed with Sirât, the Spanish movie in which a bunch of hippies in a pair of ancient Mercedes camper vans unwisely take on the punishing Moroccan desert in search of a rave. And of course I’d already seen Del Toro’s Frankenstein, Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another, and Ryan Coogler’s phenomenal Sinners – great movies all.

So why am I writing about Hamnet and not any of them? Well, because despite the acclaim that’s been thrown at it, I thought it was rather overrated. To be sure, there’s some great moments, and Jessie Buckley thoroughly deserves her Best Actress nomination for playing Agnes (Anne) Hathaway. But cumulatively, I found it to be a mishmash of heartstring-tugging cliches striving for earnestness via a tone of unremitting bleakness. I knew going in that it wasn’t going to be a bundle of laughs, but its portrayal of the grimness of 16th century life is so excessive that it often seems to tip into black comedy.

You presumably know the basic premise of the movie, based on a novel by Maggie O’Farrell – that the death, at ten years old, of Shakespeare’s son Hamnet is what inspired him to write his greatest play. It’s been described as “two hours of grief porn”, but that’s not really fair; it actually chronicles the whole time from when Shakespeare met Agnes to the premiere of Hamlet in London. Hamnet himself doesn’t actually die until a bit more than halfway through. So it’s more like an hour of grief porn preceded by an hour showing 16th century life as basically horrible.

Shakespeare himself is played by the unusual choice of heart throb Paul Mescal. We’ve seen Sexy Shakespeare before, notably as Joseph Fiennes in Shakespeare in Love, but this takes it up a notch. No trace of the Bard’s well-known baldness here; Mescal has a full beautiful head of hair throughout. At one point, he inexplicably goes for a swim in a nearby river in the rain, seemingly as an excuse to show off his very toned abs.

Now to be fair, I’ve no problem with Mescal as an actor. I’ve seen him deliver some great performances, notably in All of Us Strangers (another unrelentingly depressing movie). But he seems miscast here as Sexy Shakespeare when the rest of the movie is so determinedly grim. And of course he gets the chance to flex his actorial muscles with some actual Shakespearean lines – notably in a sequence after his son’s death where he contemplates suicide and improbably comes up with the whole “To be, or not to be” speech on the spot. Mescal tries hard, but there’s an overreverence here that leads to a rather overwrought performance.

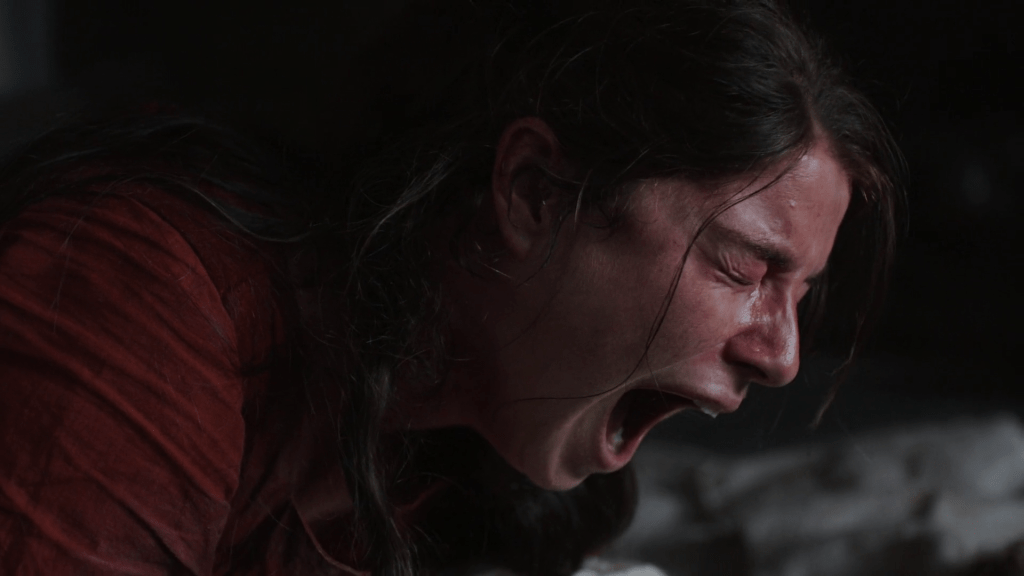

Mescal himself hasn’t been nominated for an Oscar. But that’s fair, because the movie isn’t really about Shakespeare himself – it’s about Agnes. And Jessie Buckley does very well here, giving us a performance that’s basically two hours of misery without an iota of happiness.

Agnes is a healer, in a sort of generically pagan way, and the movie is permeated throughout with a vague folk horror vibe. She gives agonising birth while wearing a bright red dress in a forest, as though she’s in an old Kate Bush video. We repeatedly see ominous shots of a mysterious black hole in some tree roots, a Freudian symbol of foreboding that’s hammered home rather unnecessarily.

Family life for the Shakespeares is, predictably, not a whole lot of fun. Disowned by their horrible families, they suffer misery after misery in a muddy, period accurate village. To emphasise the bleakness of it all, the cinematography relies entirely on natural light, giving a washed-out, stark feeling to the visuals. In case you didn’t get the message that the 16th century wasn’t a cheery time, the melancholy strains of composer Max Richter overlay events like the stillbirth of one of Agnes’ twins. The couple’s nanny never smiles and maintains an air of sanguine resignation at every point, even when Hamnet lies dying of bubonic plague; basically, we’re being told, she’s seen all this before, and it’s just what life was like.

Of course, it’s the couple’s reaction to the death of their son that the movie’s really about, even if it doesn’t happen till halfway through. And both actors give stark, almost feral performances of grief, occasionally brutal and animal in how they interact. But we’ve seen all this before in any number of dramas about the death of a child. And to be brutally honest, everything that’s happened up to this point has been so miserable that by now it’s hard to get any more depressed. You sort of get the sense that Hamnet’s better off out of it all.

Although the ultimate point of the movie is that Hamnet’s death inspired Shakespeare to write Hamlet, the Bard’s writing doesn’t really figure until the last quarter of the movie. Up till then, you could have been forgiven for thinking that his necessary dramatic role as absent, negligent father was because he was a travelling shoe salesman. Sure, there’s an early scene of him tearing his hair out (not literally of course) over heaps of discarded pages, the standard movie shorthand to show that he’s a Tortured Artist. It’s a bit like all those Ken Russell biographies of historical artists. Minus the dancing girls in SS uniforms.

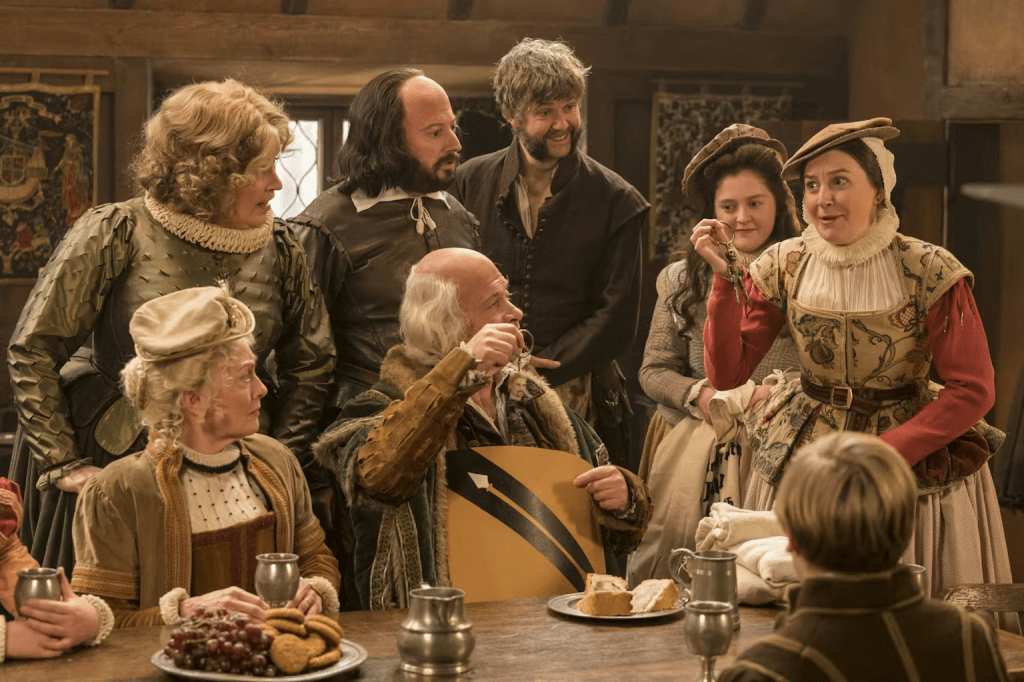

But his work is what dominates that last quarter of the movie, and it feels like a bit of a misjudgment. Up till now, it’s been a story about Agnes, but she seems rather sidelined when it becomes about Will. We see him obsessively tyrannising his actors (who are all improbably good-looking, like a 16th century boyband) to properly deliver the lines that mean so much to him. He personally takes on the role of Hamlet’s father’s ghost in the opening performance, mainly so the camera can focus on his devastated impression as he delivers lines cherry-picked from the play to seem related to his son’s death.

The scene that has garnered the most acclaim comes during this part, as Agnes, persuaded to watch her husband’s work for the first time, realises the whole play is his way of dealing with their son’s death. It’s a great performance, as Buckley goes from anger, to sadness, to a kind of acceptance. This is all emphasised by the audience’s reaction to Hamlet’s death scene, as young (and also improbably good-looking) actor Noah Jupe also gets a go at doing Shakespeare.

As Hamlet is about to die, Agnes reaches out a hand to the beautiful young man on stage, as the mournful strains of Richter’s On the Nature of Daylight tell us how to react (for about the millionth time, it seems). He takes her hand, and suddenly everyone in the audience is reaching out their hands too, united in a grief that’s no longer personal but universal.

It should be a moving moment – and to be fair, for many, it is. But to me, it seemed to be trying so hard to be moving that it descended into being blackly amusing. The much overused On the Nature of Daylight certainly doesn’t help; apparently Richter, who wrote the whole score, had an original piece for this scene, but having temped it with the familiar piece, director Chloe Zhao ultimately kept it. I stopped taking it seriously when all the earnest faces of the extras in the audience reaching out hands began to remind me of the passengers’ similar reaction to that guitar playing stewardess in Airplane.

Overall, for me, Hamnet is very much a mixed bag of a movie. There’s some great stuff in it, and it never failed to hold my attention. But it’s so laced with cliché and contrivance that I often found myself laughing when the director clearly wanted me crying. Its air of unremitting grimness actually works against it; without even one scene of actual joy, it’s hard to understand why the characters are so devastated by the death of their child. After all, their whole lives have been such a series of horrific events, why should one more make so much difference?

There’s been much scholarly debate about whether Hamnet’s death really inspired Hamlet; it is, after all, not originally Shakespeare’s story, being based on the medieval Danish legend of Prince Amleth. But I don’t really mind that the movie (and the novel it’s based on) cherry picks parts of the play to convince us of its argument. We don’t actually know much about Shakespeare’s home life, so authors can be as inventive as they like.

But for me, I far prefer the depiction in Shakespeare fanatic Ben Elton’s comedy Upstart Crow, which I found myself comparing this to throughout. That was certainly disturbing during the sex scene, where I found myself picturing the characters as David Mitchell and Liza Tarbuck. Upstart Crow’s final episode deals with the same events in a dramatic, respectful way, and they seem so much more devastating in light of the fun that we’ve seen the characters having before. This two hour miseryfest’s lack of even one moment of joy fatally undermines it for me; if I want to be depressed by literature, I’ll just go and read some Thomas Hardy.